The Plot Thickens: This caterpillar ain’t big enough for the two of us

Some of my favorite insects to find while out in the field are hawkmoth caterpillars, or hornworms (named after the characteristic “tail”). They are big, squishy sausages that often show off dazzling colors, sometimes with interesting anti-predator adaptations like eyespots and mimicry. All these characters make the hawkmoth caterpillar look like a toy just waiting for you to play with. The sad truth is that being big and flashy in the natural world often comes with a price. There is danger lurking in every corner. Despite the bright colors and adaptations, birds and lizards do not hesitate to snatch the caterpillars from branches, pathogens and spores of entomophagous fungi scattered everywhere increase the chance for passive infections, and parasitoids are always on the lookout for chunky hosts for their offspring. And the reality is that many of the caterpillars we get to encounter outdoors are already infected with something. I learned this the hard way: as a kid I used to rear a lot of butterflies and moths collected as caterpillars in the field, and many times I was devastated to witness my cute pets being reduced into a sticky mess while wiggly worm-like creatures emerge from their bodies. Sometimes I wonder how lepidopterans manage to keep their populations stable with so many enemies around.

On one of my visits to the beautiful town of Mindo Ecuador, I came across a young hornworm. Despite finding it at daytime, the caterpillar remained calm (many hornworms do their best to disappear from plain sight during the day) so I decided to photograph it.

After taking a few shots I noticed a black splotch in the photo that I didn’t like, so I decided to change the angle of view. Little did I know this was a wasp that just arrived at the leaf to check out the caterpillar. A few photos later its identity became clear: It was a species of Brachymeria, a tiny wasp that belongs to the large parasitoid family Chalcididae.

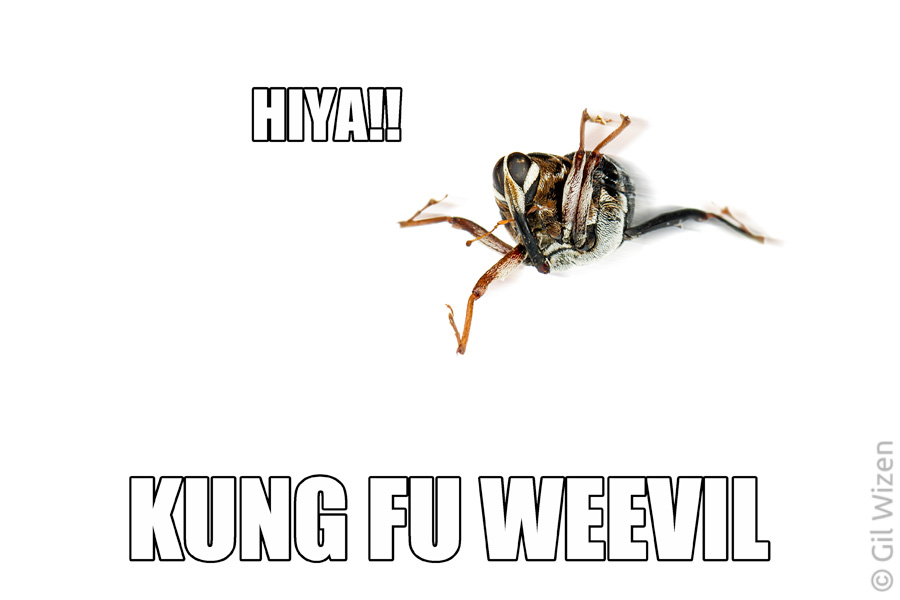

Chalcidid wasps can be easily recognized by their modified hindlegs that resemble mantids’ raptorial forelegs. The function of these structures is largely unclear. The adult wasps feed on nectar and other liquid foods, and do not use the legs for catching prey. There is a paper describing an interesting behavior in which the females use their legs in fighting over a host’s egg mass. Even more interesting are the last three paragraphs of the paper, with additional examples and hypotheses. It seems like there is no single function for these modified hindlegs and it really depends on the species and its biology. One example really stands out: “The female of Lasiochalcida igiliensis literally jumps into the jaws of antlions and holds the mandibles agape with her hind legs while ovipositing.”

Going back to our little Brachymeria and the hawkmoth caterpillar, at first the wasp just strolled peacefully on the leaf next to the caterpillar, but within a few minutes it hopped, quite literally, on the caterpillar and started walking on it, exploring its body surface while frantically moving its antennae.

In general, the caterpillar doesn’t enjoy this attention, and often swiftly moves its head backwards in an attempt to drive the parasitoid away. It usually does not work. Once a caterpillar has been spotted and marked by a parasitoid as a host, it will be attacked (here’s a fantastic video showing this behavior, notice that the fly sitting nearby is another parasitoid of hornworms – a tachinid fly!).

A closeup of the parasitoid chalcidid wasp (Brachymeria sp.) as it was walking on the hawkmoth caterpillar

As I was taking photos of the tiny wasp antennating the caterpillar, from the corner of my eye I noticed a bright yellow object flashing in. A second wasp, a golden Conura species, swooshed into the scene and started harassing the busy Brachymeria wasp.

While the Brachymeria was busy exploring the caterpillar, another wasp (Conura sp.) rushed in to fight for it

For a short while, the Conura striked from above repeatedly, yet the Brachymeria stood her ground. Eventually the Conura got fed up and attempted to grab onto the other wasp and pull her away from the host. After several tries she succeeded, and the two started swirling in the air, before the Brachymeria returned to her business on top of the caterpillar. The golden wasp did not give up and returned for a second attack and then a third.

The two chalcidid wasps (Brachymeria sp. and Conura sp.) fighting over the host. This was taken moments before the Conura grabbed the other wasp’s head and dislodged it from the caterpillar.

This was very exciting to watch, but to be honest I was waiting eagerly to see if the wasps would use their modified hindlegs during the fight. Unfortunately, I was not able to detect any special maneuvers that involved grabbing with those legs.

Why did this happen? There are several possible explanations. The simplest one is that there is a shortage of caterpillar hosts and the two wasps are competing for the same source of food for their larvae. However, an alternative explanation suggests that the caterpillar has already been infected with a parasitoid before the first wasp found it. Many chalcidid wasps are hyperparasitoids – they do not feed on the big hosts (the caterpillar) directly, but instead attack larvae of other parasitoids already feeding inside the host. In other words they are parasitoids of parasitoids.

Parasitoidception.

Watch this excellent video explaining the complex relationship between several wasp species living on a tobacco hornworm:

This can explain the intense antennation performed by the Brachymeria wasp on the caterpillar for a long period of time. Maybe the wasp was trying to determine if there are parasitoid larvae already present in there. One of the most common sights when it comes to infected hawkmoths is a caterpillar with a cluster of white silk cocoons dangling from its body. Those cocoons belong to braconid wasps, and there is a good chance that the Bracymeria wasp was after their larvae, as some species of in the genus are parasitoids of Braconidae. The golden Conura wasp could then compete for access to those parasitoid larvae or even go after the Brachymeria larvae. It can get pretty complicated with chalcidid wasps.

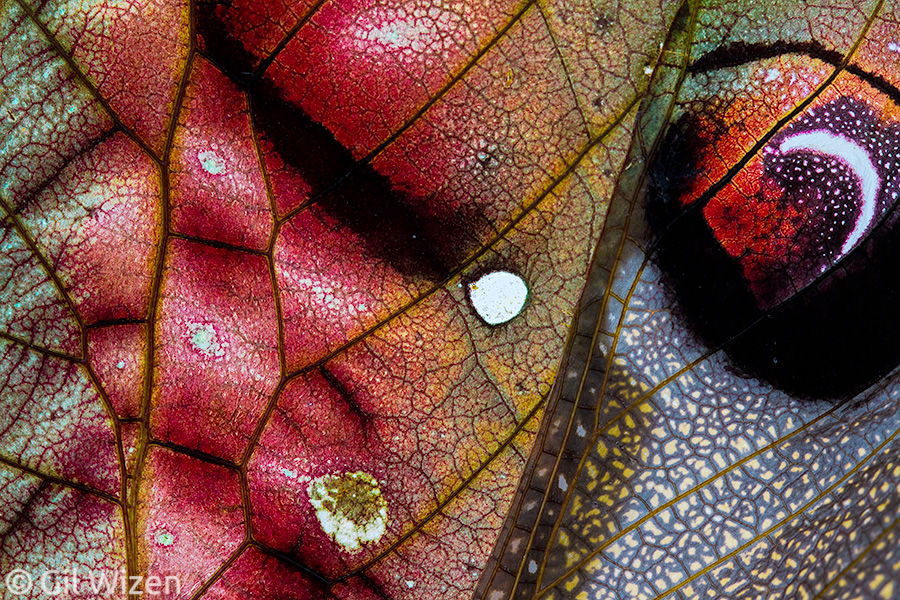

Hawkmoth caterpillar with cocoons of a braconid parasitoid wasp. The caterpillar is still alive, and can move its head to deter predators like ants and other parasitoids from approaching the developing wasps.

So who won in the end? The wasp that was more persistent. At the end of the fight the black Brachymeria wasp was nowhere to be seen, and the golden Conura wasp took over the caterpillar and started antennating it.

The interesting thing here is that members of genus Conura are usually associated with butterfly and moth’s pupae, yet the wasp here decided to chase off a competitor and take over a caterpillar.

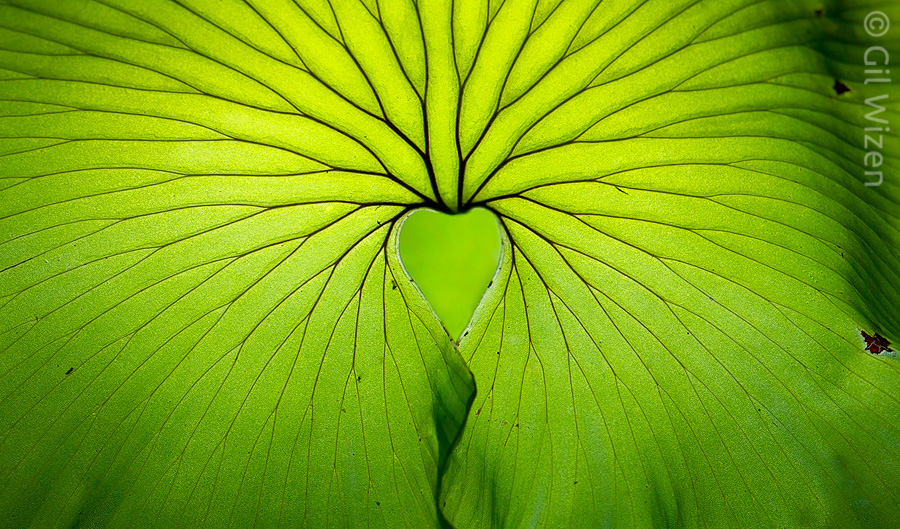

Chalcidid wasp (Conura sp.) on a swallowtail butterfly pupa. This innocent face hides a dark secret.

Unfortunately, I had to leave the scene to catch a bus so I could not continue following this interaction. Without further observations, it is difficult to say with certainty what exactly was going on between the two wasps and the hawkmoth caterpillar. Parasitoids are so diverse, and many species have such complex biology. Even though several chalcidid wasp species are being studied closely as potential biological control agents, there are far more species out there about which we simply don’t know enough!

There seems to be some confusion surrounding the term “aggressive” when describing arthropods, and animals in general. Hippopotamuses are aggressive. Some bears are aggressive. Crows can be aggressive if you injure one of their members. I think you get my point. With arthropods, I am not sure I have a clear cut example of aggressiveness. Maybe “aggressive” is not the right word. Don’t get me wrong, venomous stinging animals are still somewhat dangerous and occasionally do land people in the hospital after being stung. But I ask you, when you call them aggressive, what do you mean exactly? Aggressive to who? Anyone within the range of a nest or just anyone? Do they chase and attack people without provocation? Who took the first step? Sometimes being too close to wasps triggers their defense behavior. But then again, you really have to rub it in their face and disturb them for this alarm response to occur.

There seems to be some confusion surrounding the term “aggressive” when describing arthropods, and animals in general. Hippopotamuses are aggressive. Some bears are aggressive. Crows can be aggressive if you injure one of their members. I think you get my point. With arthropods, I am not sure I have a clear cut example of aggressiveness. Maybe “aggressive” is not the right word. Don’t get me wrong, venomous stinging animals are still somewhat dangerous and occasionally do land people in the hospital after being stung. But I ask you, when you call them aggressive, what do you mean exactly? Aggressive to who? Anyone within the range of a nest or just anyone? Do they chase and attack people without provocation? Who took the first step? Sometimes being too close to wasps triggers their defense behavior. But then again, you really have to rub it in their face and disturb them for this alarm response to occur.

In this first part of the conversation, a person leaves a comments that ticks are never beautiful, and that their existence has no justification. This a subjective statement, so I reply in the same manner. Then they go on by saying that ticks serve no purpose in the ecosystem, and that nature would be better off without them. This kind of comments makes me cringe. If an organism exists right now as we speak, it means two things: it has a well-based role in nature, and it is extremely good at what it does.

In this first part of the conversation, a person leaves a comments that ticks are never beautiful, and that their existence has no justification. This a subjective statement, so I reply in the same manner. Then they go on by saying that ticks serve no purpose in the ecosystem, and that nature would be better off without them. This kind of comments makes me cringe. If an organism exists right now as we speak, it means two things: it has a well-based role in nature, and it is extremely good at what it does. I am copying my reply because I think it is worth reading:

I am copying my reply because I think it is worth reading: