2013 in review: Good riddance!

In response to Alex Wild’s call in Scientific American, here is my list of “2013 photographic achievements”.

I thought about how I should start this. I want to say that 2013 was a crazy year. But if you read many of these “year-in-review” posts you will soon find out that they are very repetitive, usually starting with “this was a _______ year for me” (insert your favorite adjective: crazy, busy, intensive, productive). I would like to try something a bit different:

2013 was the worst year I have had. Ever. Here is a partial list of my mishaps – got a warning from my university department for trespassing overseas, got my face broken while doing research and went through a reconstruction surgery, had my luggage searched extensively by airport customs officials on my way out of NZ, got a warning for having 300ml 70% ethanol for research in my one of my bags prior to flight, was mistakenly charged the $1000 excess fee upon returning a rented vehicle (twice!) and got my credit card locked, had my PhD research terminated and lost my main source of income, dealt with overseas bureaucracy, broke my main flash unit a few days before a photography workshop, got the return flight cancelled a day before I left the country for the workshop, served as a host for six internal parasites, and the list goes on. I saved you from the gross bits.

So you can understand why I am eager to wave this year bye bye. Don’t get me wrong, a lot of good things happened too – I met new interesting people, I learned and experienced new things and I finally attended BugShot macrophotography workshop in Belize – an event that will surely remain as a good memory for years to come.

And now without further due, here are my best-of-2013:

The photo that got me into the most trouble

This is definitely not one of my best photos. I do not like the light, the composition could be a lot better, and I could have improved the focus. However, it is an important behavior shot.

This photo was taken during my PhD research trip in New Zealand, in which I was recording the mating behavior of ground weta. The male, under the female, has finished depositing the sperm ampulae on the female’s genitalia (white blobs) and is preparing for depositing a nutritious nuptial gift close to her secondary copulatory organ. Unfortunately, this series of photos caused a dispute regarding image use and copyright and had cost me great pain. [Stay tuned for “My NZ ordeal (part 2)”]

The most unpleasant subject

I have always been interested in the fuzzy botflies and their biology as internal parasites of mammals, and I have been waiting for an opportunity to photograph a larva. This year, I got my chance when a former student collected one from a rabbit. I think this creature is amazing, but I could not bring myself to accept that this larva was burrowing into the flesh of a live rabbit just a few days earlier. Little did I know that I would become a host of several such larvae just a couple of months later…

The best landscape shots

This photo was a real game changer for me. My photography has changed substantially through experimentation during the trip to New Zealand. I decided to make a quick rest stop from a long drive at the waterfalls, and took only my camera and a fisheye lens with me. This is ended up being one of the best photos I have ever taken. Not only it is completely hand-held with no help of filters, I also managed to squeeze in a sun-star in between the top trees. After this I realized how much I know about photography and that I am already at a good level (before this I always thought I was not good enough).

Slope Point is known as the southernmost point of the South Island of New Zealand. Because of its close proximity to the South Pole, extremely intense and uninterrupted winds from Antarctica blow and smash into the trees here, severely disturbing their growth and forcing them into twisted shapes.

The most perfectly timed photo

I did not plan taking any photos that morning – it was pretty rainy with a thick overcast. I was walking a friends’ dog up a hill when I suddenly saw the sunrays breaking through the clouds. I ran back to the house and grabbed my camera. The only lens that was effective to record the scene was my Canon 100mm f/2.8L Macro, so I panned and took 42 shots and stitched them together later to get a high quality super-image.

Best behavior shot

One of my main goals in documenting ants’ mutualistic relationships was to photograph an ant collecting a drop of honeydew from a tended homopteran (aphid, scale insect, plant hopper etc’). I have tried to do it many times, but was too slow to “catch” the drop. You can imagine my enthusiasm when an opportunity to photograph a tending wasp presented itself!

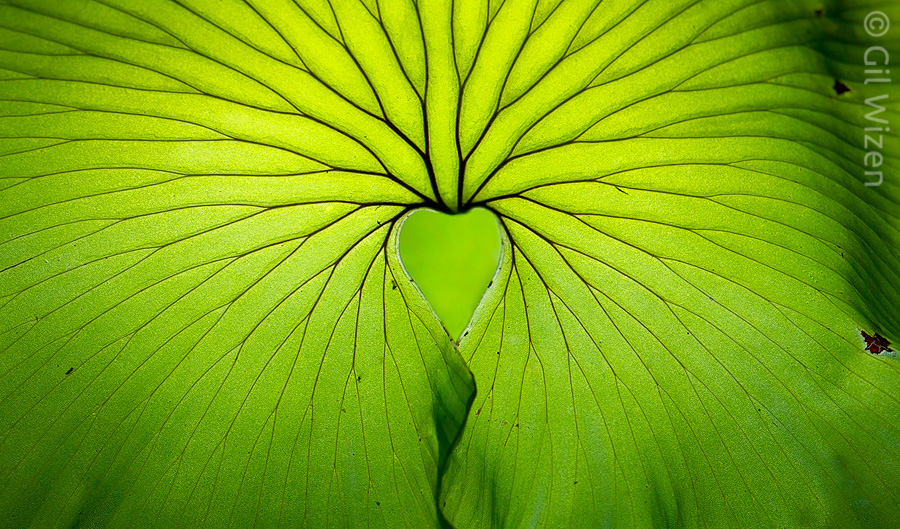

The best non-animal photo

I hate to admit it, but I am biased about my photo subjects. When photographing, most times I will prefer a small animal subject to a plant or scenery. I lost many good photographic opportunities in the past this way. But every once in a while I come across something so different, so unique, that it blows my mind. This species of filmy fern from New Zealand is such a plant.

The most cooperative dangerous subjects

This male scorpion was so tame while being photographed that it was tempting to try and handle it. Only afterwards I found out that this species possesses quite a potent venom, and is even responsible for several death cases in Central America.

One of my “most wanted” for 2013, and I almost gave up after looking for it unsuccessfully for several nights during my visit in Israel. Luckily, just when I was about to leave the dunes, I found this beautiful male snake a few steps away from my car. It did a defensive display upon noticing me but later calmed down and stayed still, allowing me to frame a nice close-up portrait.

The best photo of an elusive subject

This photo could be a deserving candidate for “the photo that got me into the most trouble” category, however the troubles found me not as a result of taking the photo, but more because I was hiking in the geckos’ highly protected habitat looking for them. All in all, I am very glad I got a chance to see these gorgeous reptiles, and hope they live long and prosper.

The best natural phenomenon observed

There were two recent outbreaks of desert locusts in Israel (originating in Africa): in November 2004, and March 2013. Unfortunately for me, I missed both. However, two months after the swarms were exterminated billions of locust eggs started hatching and feeding on any green plant, causing damage to several crops in their way. I was extremely lucky to be in Israel during this time, and I managed to photograph and record the juvenile locusts before the order to exterminate them took effect.

The best focus-stacked shot

I have been manually stacking images for some time now to get deeper depth of field in macro photographs, but had mixed results. This trapdoor spider came out very nice, revealing good detail in hairs and claws.

The best wide-angle macro

I had my eyes on this technique since 2005, but I never got myself to actually try it. Inspired by Piotr Naskrecki’s books and blog I decided to look more into it:

One of my first attempts to shoot wide-angle macro using a fisheye lens and a fill-flash. Now I know I was doing it “wrong” (or differently from my inspiration), but even so, the photo came out quite nice and received a lot of attention. The only things I wish the photo would also deliver are the strong wind and the loud cicadas singing in the background.

This is one of Israel’s largest katydid species (only Saga ephippigera is bigger). I always wanted to have a wide-angle macro shot of Saga, showing its large head and spines. However, in the end I decided not to move too close to the katydid, giving the impression that it is about to step out of the photo.

This photo would not have been possible without the help of Joseph Moisan-De Serres who gave me informative advice about orchid bees, and Piotr Naskrecki, who encouraged me to attempt a wide-angle shot of them. It took a lot of time and patience to get the “right” shot; I suspect this was also the time when I got infected with the human botfly.

The most exciting subject

To me, there is nothing more fun and rewarding than discovering something new. This is one of three potential new species of whipspider (genus Charinus), found in Israel this year and currently being described. Whipspiders (Amblypygi) have become one of my favorite groups of arthropods in the last years and I hope to learn more about them!

So in conclusion, out of these, which is my most favorite best photo of 2013?

The answer is none.

There is another photo that I like better than all of these, one in which I experimented in a technique I know absolutely nothing about and got a lovely result. However, I will leave that photo for my summary of BugShot Belize, which hopefully will be posted before the next BugShot event!