Little Transformers: Deinopis, the ogre-faced spider

Today’s Little Transformer is a little unusual. First off, it is a spider. This spider is so unique in its appearance and behavior that I am surprised it has not inspired any exaggerated depictions in popular culture. It spends most of its time hidden, posing as a harmless twig among the forest vegetation. It is so good at what it does, that unless it moves it would be very easily overlooked. However, when night falls this seemingly harmless twig transforms into a sophisticated killing machine. Meet Deinopis, the ogre-faced spider (also known as net-casting spider).

Net-casting spider (Deinopis spinosa) frontal view. Their eye arrangement is one of the weirdest of all spiders. Notice the lateral eyes are pointing down!

Ogre-faced spiders are found on every continent except Europe and Antarctica, but they occur mostly in warm regions of the southern hemisphere. Found primarily in Latin America, Africa, Madagascar, and Australia, these spiders all share the same appearance: brown color, elongated body with long forelegs, and an unmistakeable face. The small family Deinopidae contains only two genera: Deinopis, holding most of the species, and Menneus.

Interesting texture and patterns on the dorsal side of a net-casting spider (Deinopis spinosa). The legs are held tightly to form a typical ‘X’ shape at rest, making it look like the spider has only four legs.

Deinopis are very unique among spiders for having superb vision, thanks to their huge median eyes.

Net-casting spider (Deinopis spinosa). Those eyes… You can now understand why they are called ogre-faced spiders.

A closer look at the median eyes of a net-casting spider (Deinopis spinosa). Staring straight into your wretched soul.

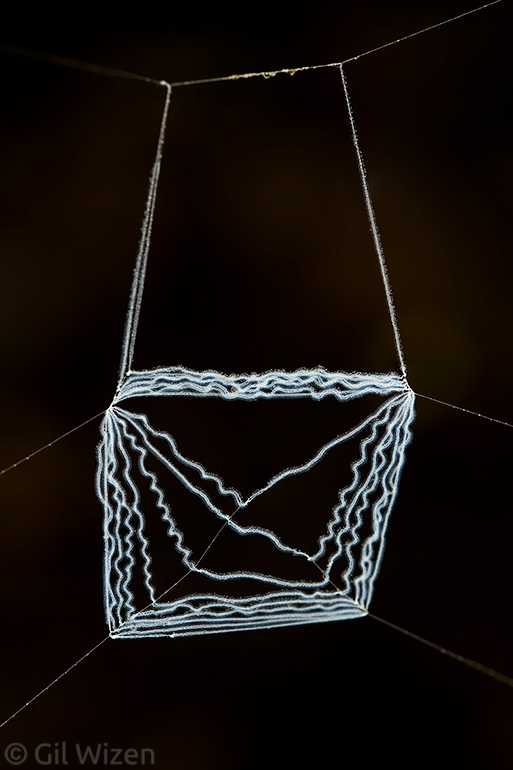

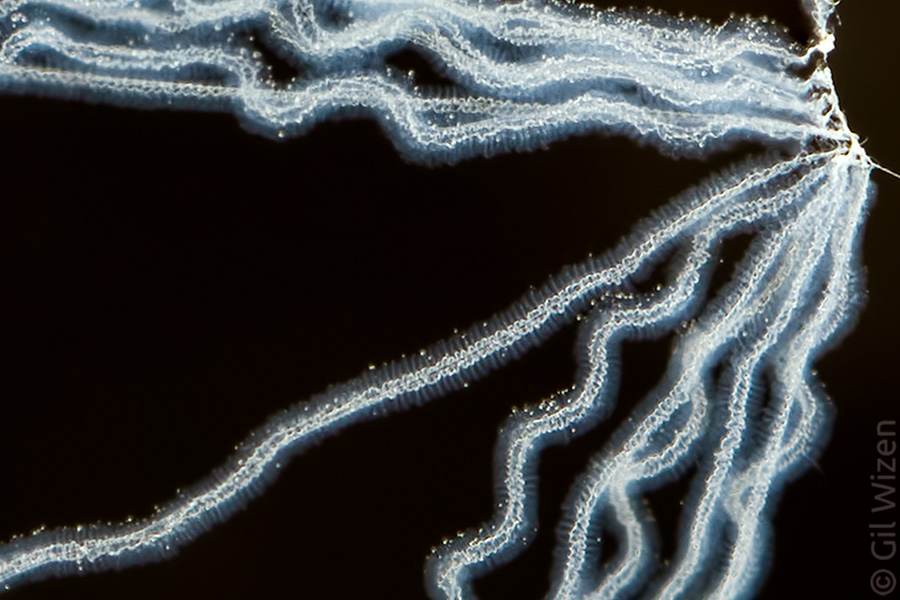

The big eyes are what gave these spiders their common name, and they are so big that it is easy to miss the other six eyes on the spider’s head. I did my best trying to capture the stone-cold expression on a Deinopis spinosa face, but also check out Michael Doe’s amazing work with the Australian species D. subrufa. These median eyes are extremely sensitive to light, despite lacking any reflective tissue behind the lenses. Instead, a light sensitive membrane is formed inside the eyes every night, and then gets broken down at dawn. This allows the spiders to track subtle movements in complete darkness during their activity hours, something that is essential for their unique hunting strategy. While somewhat close to other weavers, ogre-faced spiders do not construct a fixed web to trap their prey. Instead they make a rather small hand-net, a handkerchief if you wish, that they use to catch insects passing nearby. The silk constructing the net is not sticky but extremely fuzzy and flexible, thanks to a special comb-like structure on the spider’s legs that stretches and frizzle the silk as it is coming out of the spider’s spinnerets.

A closer look at the net reveals the woolly silk used to make it. If you look carefully you will notice that it is coiled like a spring, allowing the silk to be stretched and expanded to completely cover the prey.

The spider usually shapes the net as a square, and holds it loose over a branch or a leaf where an insect is likely to walk.

Once it spots a suitable prey, the spider quickly stretches the net and snatches the passing insect by hand. The net can be stretched and expanded up to five times its original size without being torn, thanks to the special attributes of the silk. It entangles anything it touches. The spider is extremely fast in its response that sometimes it succeeds in capturing passing insects in mid-flight, again – completely by hand. You have to appreciate the speed and accuracy that goes into this hunting technique.

Net-casting spider (Deinopis sp.) ready for an insect to pass on a nearby branch. These spiders usually place themselves right above a possible walkway for arthropods. Photographed in Ecuador

It is relatively difficult to witness this behaviour in the field, mainly because by observing at night we add another component to the equation – light. In fact, in all my trips to Latin America I have encountered these spiders many times, but only once I was able to see the spider hunting… and totally missing the prey insect. So you can imagine my excitement when I realized I was going to work with one of the species, Deinopis spinosa, while it is on display at the Royal Ontario Museum’s “Spiders: Fear & Fascination” exhibition. For several weeks I tried to get a glimpse of it feeding but without success. One day I decided to toss a cricket close to it before leaving the exhibit area and within a spilt second the spider responded and caught it! I was in awe. I had to find a way to record it on video for people to see. I enlisted Daniel Kwan, one of my colleagues at the museum who has more videography experience, and we set out to produce a short movie. It took us many attempts to get decent footage of the hunting behaviour. Many times the prey crickets tried to hide, and occasionally the spider would respond to them but miss. Even though feeding the spider in an artificial environment means we had more control, it was really difficult. It makes me wonder how long the spider must wait in the wild until it is able to catch a meal.

Also worth mentioning is genus Menneus from the same family. These spiders are much smaller than Deinopis and they lack the large median eyes, therefore they are not true ogre-faced spiders. However, they spin a catch net and use the same strategy for hunting prey. The genus contains only a handful of species, distributed mainly in Australia, but with some representation in Africa. Some of the species are quite beautifully patterned compared to the plain-looking Deinopis, and there are even green-colored species! You can find some photos of Menneus spiders at the bottom of this page.

Something I was thinking about while writing this post – why do I never encounter small deinopids in the field? It would be really cute if they had miniature nets for catching even smaller insects. Even when I look for information online and in the literature, it only concerns medium-sized juveniles and adults. Could it be that the small ogre-faced spiders actually have a different hunting strategy than that of larger individuals?