Insect art: Whip spider tattoo

Looking back at my posts about arthropod-inspired art, I’ve covered natural history illustration, monster and character design, animated media, sculptures, taxidermy, and even rubber stamps. I find it surprising that I have not written anything about tattoos so far. Not only are insects and arachnid tattoos fairly popular and commonplace, but on a more personal level my first exposure to arthropod tattoos takes me back to my teenage years – My brother showed up one day with a large black widow spider tattooed on his front left shoulder… a spider that I drew on paper only a few weeks earlier. You can imagine my surprise as a 13-year old, realizing that my brother decided to permanently have one of my early drawings on his body, not to mention I never considered that particular drawing to be good, thanks to my imposter syndrome. To make a long story short, for a while afterwards I examined tattoo magazines in search of inspiring pieces and later helped designing more tattoos for my brother as well as other people. Which brings me to today’s post: designing and inking a whip spider tattoo on my friend Peggy Muddles, aka The Vexed Muddler.

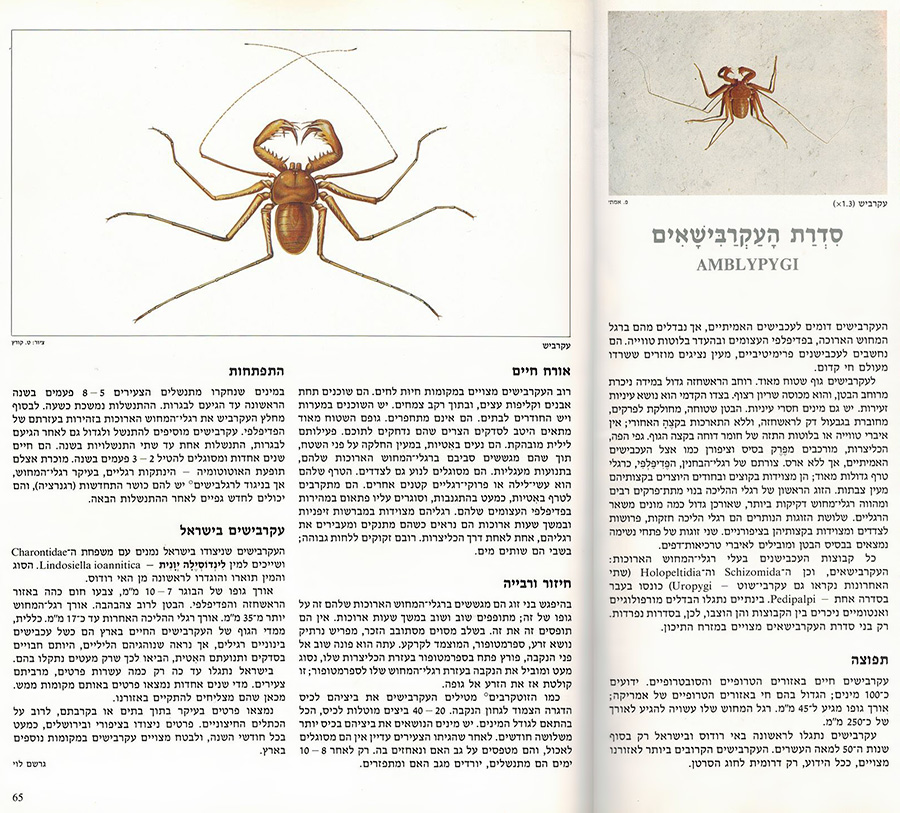

The idea was to tattoo a bluish Charinus israelensis, a species that I discovered and the topic of this blog post. But why blue? If you look through my photos of Amblypygi, you will probably notice that most of them have dull colors, and members of genus Charinus in particular are typically orange-brown in coloration. During molting, however, Charinus comes out entirely white in color due to minimal pigmentation, and gradually turns bluish-grey as time passes, eventually becoming brown once its exoskeleton hardens. The teneral stage shows not only blue-teal tones but also a lot of fiery orange-red color on the bristles and mouthparts. This classic orange and teal contrast is what led Peggy to select the species, followed by choosing a complimentary plant: Cyclamen coum, a tiny protected species that occurs in the same areas where the whip spider is found.

We sent some reference photos to the talented Jacqueline Pavan, who owns Storm Horse Tattoo in Toronto, and after some brainstorming we settled on a detailed design.

This is not Peggy’s first tattoo, by the way. Her back right shoulder tattoo was loosely based on a framed Goliath beetle specimen I made a few years ago (although a different species). Designing that piece was a collaborative effort together with Jacqueline. It combines Peggy’s love for microbes, space, and insects, resulting in what is in my opinion one of the best tattoos ever made. You just have to stare at it. It’s a lot to take in.

Back to our whip spider tattoo, I decided that I want to be present when it is being applied. No doubt I was curious about how it is going to turn out, but I also wanted to make sure some important details are preserved since we are dealing with real existing species. Now, I have walked in on people midway through their experience of being inked before, but this time I had a chance to sit through the entire process, from preparing the workstation to the last drop of ink injected. Joined by Catherine Scott and Brian Wolven, we spent our Saturday afternoon with Peggy at Storm Horse Tattoo, getting her Charinus israelensis tattoo! How exciting!

As preparations began, one of my first thoughts about Storm Horse Tattoo was ‘this has got to be one of the cleanest studios I have ever seen’. Everything is so well-organized and spotless, it’s already my cup of tea… I don’t know why but every time I think about tattoo studios I imagine blood splashes on the walls. It is possible that I’ve watched too many gory movies. Anyway, I decided to document the inking progress, hopefully you’ll find it interesting.

Before inking, a stencil was prepared to transfer the design onto the skin and confirm the best placement for it. This was also the time to make sure Peggy is aware of and understands the cultural implications of her subject of choice hehe (sorry, it’s my twisted sense of humor).

Then black ink was applied to the outlines of the design.

At this point Catherine showed up and gave us an update about her black widow tattoo that she had done a week before to celebrate her PhD defense. Her amazing piece was designed by non other than Thomas Shahan!

After sunset I noticed the light changed dramatically inside the studio, and I couldn’t help thinking how much the workstation now looked like an old operating table. I’m getting strong 17th century vibes from this photo. Think “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp” vibes.

Slowly getting there. The plant is finished, now to add shade and color to the whip spider.

In this photo the whip spider’s abdomen is a little too green. Peggy caught that, and we fixed it in post.

Tattoo sessions can be quite long in duration, so in order to keep everyone entertained Brian started reading astronaut stories about life in space. This resulted in one of the weirdest photos I have ever taken of someone. Viewed out of context, this will probably provoke many questions.

“They had to use the robotic arm to break off a two-foot-long icicle of frozen urine and wastewater that was dangling from the space shuttle”

In case you were wondering, working accurately on the tattoo was made possible by using references. In this case, a line art draft of the original design and a photo reference for the colors.

Getting the right shades and highlights of all the different colors is a long process. It was so mesmerizing to see Jacqueline breathing life into these drawings.

The last step was to apply a little bit of white ink to emphasize the arachnid’s lateral eyes and spikes.

And voilà!

The finished piece is simply stunning, I dare say. Jacqueline did an amazing job with the information she received. I remind you that she is an artist, not a scientist, and she didn’t know that these arachnids even existed before taking on this project. The result is a morphologically accurate Charinus israelensis and Cyclamen coum plant. I’m surprised that I like the plant even more than the whip spider!

A closer look at the finished Charinus whip spider and Cyclamen tattoo. I’m super impressed and proud at the same time.

As I was sitting at the studio observing the inking process and listening to a mixture of needle buzz and astronaut tales, I noticed something interesting. I do not have tattoos on me and have never considered getting any. But I found that if you sit long enough in a tattoo studio while someone else is getting theirs done, you ease into the idea that ‘hey. it’s not so bad. I guess I can get one too at some point’. Am I going to? Nah, probably not. But I found the whole experience of following Peggy’s journey quite eye opening. I definitely learned a lot from this, and I’d like to take this opportunity to thank Peggy and Jacqueline for being kind enough to let me stick around and watch. And thank you for choosing my whip spider for your tattoo, it makes me so happy!