Amphibians are tougher than we think

A few years ago I wrote a blog post about a dream of mine that came true – seeing the gorgeous tree frog Cruziohyla craspedopus in the wild. Even after numerous trips to Ecuador I still consider it one of the best moments I have experienced in the outdoors. Fast forward to this week, I am excited to present a new paper I published about these frogs in Herpetology Notes.

To summarize this already short paper – the fringe tree frog (C. craspedopus), an amphibian often used as an example for species requiring pristine habitats, made itself a habit to breed in human-made infrastructure containing polluted, sewage-like water. And not only that, but the frogs are also perfectly fine with this, recruiting healthy new individuals into the population and returning every year to the same spot for more breeding.

Fringe tree frog metamorph (Cruziohyla craspedopus), still with its tail, climbing out of a septic tank

On the surface this is a simple natural history report that adds to the existing knowledge about the species. However, when you look at the bigger picture there is something else hidden between the lines.

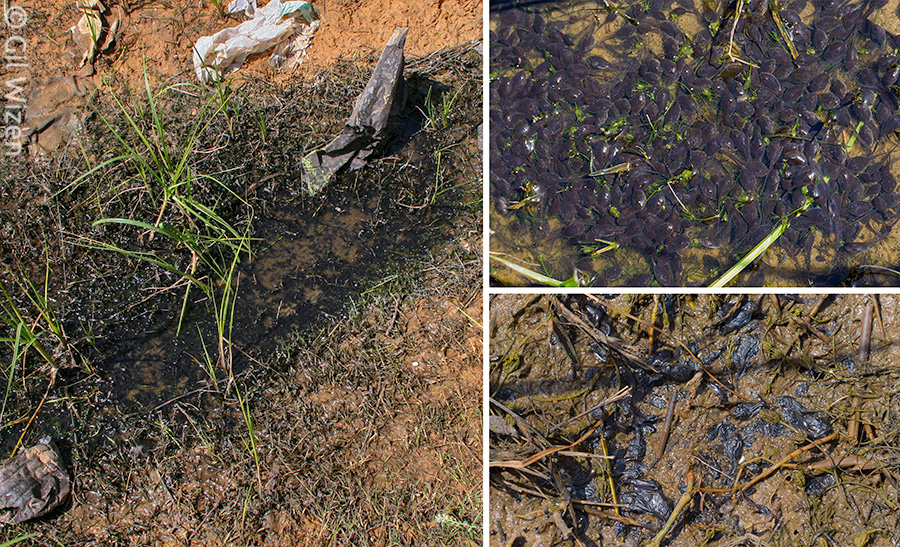

Remember back in the day when I had to sacrifice amphibians in the name of science? One of the questions that I get asked often is ‘how was this research ever approved by an ethics committee?’ After all, amphibian populations suffer a global decline, caused by various different factors: habitat loss, climate change, diseases, invasive species, etc’. Surely killing hundreds of them for science would seem like defeating the purpose of their conservation. But what if… those amphibians were never meant to be alive in the first place… You see, for the Epomis research we selectively collected tadpoles from areas where they were destined to die. These included flooded vehicle tracks, deep water holes with no climbing surface, and shallow puddles in the process of drying out. We called them “ecological traps”: sites that seemed suitable for amphibian breeding but failed to provide the right conditions to support the growth of tadpoles, or did not hold water long enough to allow for their complete development.

A classic ecological trap for amphibians: a puddle in the process of drying out, containing hundreds of tadpoles. The next day they were all dead. Photographed in Israel

But why do amphibians choose to breed in those dangerous sites in the first place? What can I say, amphibians are idiots. Or are they? Maybe it is just their way of ensuring the survival of their species, and we are interpreting it the wrong way?

The species that breed in ecological traps are usually ones with an explosive breeding strategy: migrating to the breeding sites only for a short period of time during a specific season, and offloading massive amounts of eggs in the water, sometimes up to ten-thousands of eggs per female. With so many eggs being produced by each female, they have nothing to lose. One breeding site may fail to provide the right environment for the developing tadpoles, but others will do fine. Or, some of the tadpoles might grow faster than others and complete their metamorphosis before it is too late.

Not too many people are aware that juvenile fringe tree frogs are often active during the early morning hours. Here is one climbing up to the canopy.

Back to our fringe tree frogs in Ecuador: the species is an iconic frog, representing a true Amazonian amphibian, with its unique appearance and behavior. To the best of our knowledge it is not an explosive breeder. It is reported to breed in tree holes and in water reservoirs under fallen trees, while spending the rest of its time high up in the thick tree canopy. For many it is considered elusive and hard to find. But in reality these frogs could not care less about the condition of breeding sites or water quality. Just like the aforementioned explosive breeders, while on their search for suitable water reservoirs the frogs can stumble upon something that in their eyes has potential for breeding, and they will test it. This means that to us, it may look like they are choosing the “wrong” place to breed. But what if they are right and we are missing something? Before encountering the frogs described in the paper, I would have sworn that they have no chance at successful breeding in polluted water at an unnatural or disturbed habitat. Not to mention doing it over the course of several consecutive years. And what do you know! They sure proved me wrong and I learned something new. Don’t get me wrong, amphibians still need our constant attention. I am not saying that we should stop our efforts to conserve amphibian species and save them from extinction, but maybe we should cut them some slack. Because even though they are fragile creatures, sometimes they are tougher than we think.