Cruziohyla sylviae – almost closing the circle

UPDATE (23 Jan, 2020): Since publishing this article in 2017, the genus Cruziohyla has been revised and its taxonomy has changed. The genus now contains three species. The species described here was redescribed and is now named Cruziohyla sylviae. The following text has been corrected accordingly.

Over three years have passed since my unforgettable encounter with the fringe tree frog, Cruziohyla craspedopus, in the Amazon rainforest of Ecuador. That experience is still one of my all-time favorite moments of working in the field. Since then, I learned a lot about this species and nowadays I see them every time I visit Ecuador (as you can probably tell by their growing presence in my frogs gallery). Still, even after all this time the fringe tree frog remains high up on my list of the world’s most beautiful tree frogs. But it felt like something was missing. I decided to take a trip to Costa Rica, and right from the start I had one goal in mind: to find one other third of genus Cruziohyla – Sylvia’s tree frog (Cruziohyla sylviae).

After researching a little on C. sylviae’s distribution, I decided to contact the place that in my mind packed the best potential of seeing one. The Costa Rican Amphibian Research Center (neatly abbreviated C.R.A.R.C.!) is a small biological research station located close to the Siquirres River in the Guayacán rainforest reserve, in Limón Province. It is owned and run by Brian Kubicki, a conservation naturalist who dedicated his life to the study of Costa Rican amphibians, with special focus on glass frogs, poison frogs, tree frogs and lungless salamanders. I thought if there is one person that can help me find C. sylviae in Costa Rica, it must be him. Remember the frog poster from 2003 that I mentioned in the beginning of my post about C. craspedopus? Brian Kubicki was the person signed at the bottom of that poster. Now how cool is that.

To begin with, the C.R.A.R.C. Guayacán reserve is stunning. There are many interesting corners with different types of microhabitats, so a huge potential for finding interesting reptiles and amphibians, not to mention arthropods. Unfortunately for me, I arrived to the reserve during a dry spell, as it has not rained for days prior my arrival, and most habitats that were not directly connected to natural springs or the river were fairly dry. Even so, I still found the place highly biodiverse, and recorded many interesting species of arthropods, some of which I have not yet had the chance to see in the wild.

Alas, I was there to find C. sylviae, and I was worried that the area might have been too dry. Brain kindly offered to hike with me at night and show me some good spots to find specific amphibians. And it did not take him long; once we hit a certain trail he found C. sylviae within minutes! What a gorgeous species. I will just paste here my description of C. sylviae from the post about its sister species:

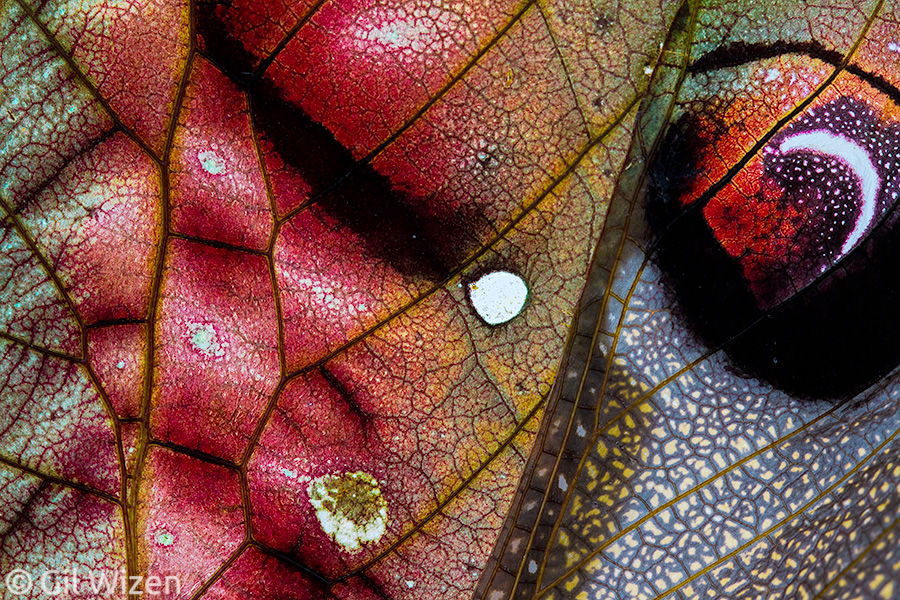

“…a massive tree frog, with eye-catching coloration: dark green (dorsal) and bright orange (ventral). The sides of its body are finely striped in black against an orange background. Its eyes, featuring a vertical pupil – an indication this animal has a nocturnal lifestyle, are orange with a grey center. In addition, the foot-webbing is wide and the adhesion discs on the fingers are large and round, giving it a cutesy appearance.”

This tree frog species is indeed splendid. It was exactly what I expected. The frog we found was a female, and I was surprised how robust it was. It is not every day you get to see an amphibian that is both colorful and big.

As mentioned, we found the frog at night. However, I wanted to see if I can locate it myself so I went back to the same spot in the morning. Let me tell you, it was not easy to find it in daylight. Not only it is difficult to find a green frog in the “sea of green” which is the rainforest, but also the tree frog is hunkered down and blends perfectly with the leaf it is resting on. After some time searching I thought about giving up, but then I looked up. I saw the perfect silhouette of a resting frog on one of the palm leaves, backlit by the sunrays penetrating the rainforest canopy. This could have still been an optical illusion created by a fallen leaf casting the silhouette. Yet, it was indeed C. sylviae. I couldn’t be happier.

To me, seeing Cruziohyla sylviae in the wild is one step closer to closing the circle on a journey that started over a decade ago in a backpacker’s hostel in Costa Rica, continued in the Amazon rainforests of Ecuador, and returned to Costa Rica again. Maybe one day I can travel to the Choco region of Ecuador to search for the third and final piece of the puzzle – the splendid leaf frog Cruziohyla calcarifer.

Sylvia’s tree frog (Cruziohyla sylviae) and fringe tree frog (Cruziohyla craspedopus). I wish moments like this one were possible in real life. Unfortunately, such a gathering of the two species is impossible. Cruziohyla sylviae’s distribution is restricted to Costa Rica. And even though the other Cruziohyla species both occur in Ecuador, they are separated by the Andes Mountains: C. calcarifer occupies the northwestern slopes, while C. craspedopus is found in Amazonian lowlands on the eastern side.