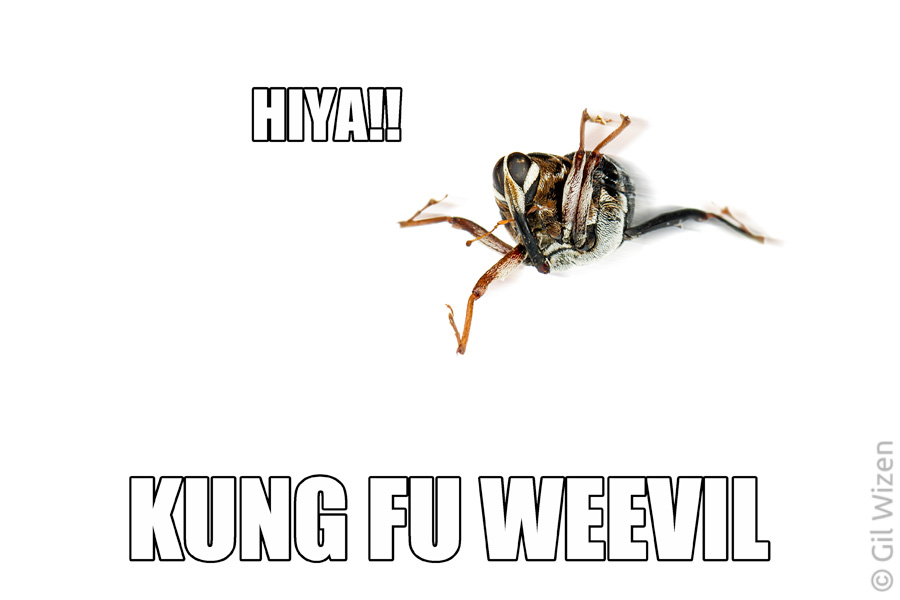

Wildlife Photographer of the Year Q&A: Beautiful bloodsucker, Behaviour: Invertebrates highly commended

Part 3 in the series of Q&A posts about my Wildlife Photographer of the Year winning images is Behaviour: Invertebrates highly commended: Beautiful bloodsucker.

Beautiful bloodsucker. Wildlife Photographer of the Year, Invertebrate Behaviour category highly commended. A female mosquito (Sabethes sp.) in mid-bite. Amazon Basin, Ecuador

You can watch the part when it appears in the awards ceremony here (timestamped)

“Beautiful bloodsucker” is my personal favorite among my winning images, maybe because it took the greatest effort and longest time to produce (more on that later). This photo was released in September 2021 as a teaser for the Wildlife Photographer of the Year awards ceremony along with several other finalist images. Interestingly, upon release most media outlets chose to ignore the photo and omit it from their reports, however it eventually received exposure thanks to a BBC article that covered it extensively. The photo went viral online shortly after, as “the world’s most beautiful mosquito.”

“Now, come on. Come on! That’s the finest mosquito you’ve ever seen. It looks like a fantastic piece or art deco jewellery”

You can also read the CBC article about “Beautiful bloodsucker” here or listen to my radio interview.

Why is this mosquito so flamboyant?

It is not clear why Sabethes mosquitoes have such beautiful metallic colors, but they are not the only ones. Other mosquitoes (for example Psorophora cyanescens, Toxorhynchites, etc’) have blue metallic scales covering their body. I discussed the fuzzy leg ornaments in a previous blog post; it is believed that they play a role in courtship, but because they are present in both sexes it is not well understood how they are being used.

What are those curvy things above the mosquito’s head?

Those are the mosquito’s hind legs! All mosquitoes curve their hind legs upwards at rest, occasionally swinging them from side to side. These legs are covered with fine hairs and function as sensory organs to detect approaching threats. When an intruder (or a swatting hand) gets close, the legs detect the movement by changes in the air currents above the mosquito, prompting it to escape immediately by taking off.

What is the size of the mosquito?

Despite their exotic appearance, Sebethes mosquitoes are not too different in size from your typical mosquito. They are 4mm long, very tiny. The one photographed in my winning photo “Beautiful bloodsucker” is standing on my finger knuckle. Here is one photographed on my pinky finger for a better sense of scale.

Do you normally let mosquitoes bite you?

Not by choice, but when you are visiting a tropical rainforest it is bound to happen. Especially after rain, small water reservoirs in trees, epiphyte plants, or fallen leaves fill up and trigger female mosquitoes to go out looking for a blood meal before laying their eggs. I normally try to avoid getting bitten by wearing long sleeve clothes and putting some bug spray, but it is pretty impossible to avoid them entirely in the tropics. You can protect yourself as much as possible, but the moment you are distracted they will seize the opportunity to sneak up on you. Sabethes is the only mosquito towards which I am more forgiving. I love these mosquitoes, and every time I encounter them on my trips to South America I cheer with joy and hope that they come closer for a bite so I can take more photos of them. Am I a masochist? …maybe.

Isn’t this risky? Can this mosquito transmit any diseases?

It is important to remember that this is a wild animal, not a mosquito that was reared in a lab free of pathogens. There is definitely a component of risk here, as with all wildlife. These mosquitoes are important vectors of several tropical diseases, such as yellow fever and dengue fever, and perhaps other diseases as well. While taking the photo, I was bitten by this mosquito and several others, increasing the risk of contracting a vector-borne tropical disease. But I am still alive!

Is a bite from this mosquito painful?

Very. Every bite from a given species of mosquito feels a little different, mostly due to size and other morphological differences, but also thanks to differences in composition of the mosquito’s saliva. Sabethes mosquitoes are really something special. Not only do you feel them drilling into your skin, but it also leaves a painful sensation lasting hours and even days after the bite.

This Sabethes mosquito was photographed at the same location as the others, but it appears to be a different species with different leg ornaments.

How long did it take you to get this photo?

About 4-5 years. I planned this particular photo composition for a long time. I have been encountering Sabethes mosquitoes for almost a decade and I knew I wanted something very specific. Little did I know that it would take an unbelievable amount of preparation and patience. These mosquitoes are extremely skittish and difficult to photograph well, especially in the constant heat and humidity of the rainforest. The mosquito responds to the tiniest of movements and to changes in light intensity. This means you must stay very still while attempting to photograph it, and also be prepared for the mosquito’s escape if using a flash. Fortunately, you are never alone with a single mosquito, because usually there are dozens of them hovering over your head. After carefully studying and observing the insect’s behavior for several years I was able to get a head-on, intimate photo of a female mosquito preparing to bite one of my finger knuckles. Even on the successful shoot itself it did not go smoothly the first time, and I had to keep trying for a couple of hours, all while getting bitten, until I finally got the photo I had in mind.

Why does this photo look like it was taken in a studio?

That is a great question that I received more than once. Indeed the background in “Beautiful bloodsucker” looks very plain and uniform to be considered in situ (in other words, a photo that was taken on site, in the subject’s natural habitat). However, I assure you that it was taken in the rainforest while I was visiting Ecuador. The background is simply the sleeve of my long hiking pants. After experimenting with different backgrounds on previous photography attempts, I chose this neutral background to emphasize the full spectrum of colors on the mosquito’s body.

Do you have any behind-the-scenes photos?

I do not, but maybe this it for the best. Almost every time I attempted to photograph these mosquitoes I was surrounded by a swarm of them. It was very annoying and I was frustrated from getting bitten. I bet it would look horrible on camera.

Do you think this photo will change people’s general view on mosquitoes?

I am a pretty realistic guy, so I do not expect my photo to make people fall in love with mosquitoes. My hope is that it will make people pause and look before they automatically swat a mosquito, and maybe appreciate and beauty and structural complexity of these animals.

We like the photo! Can we buy a print from you?

Of course. You can get a wall print of “Beautiful bloodsucker” directly from the Natural History Museum’s shop at affordable rates. If you need something different, contact me and I will do my best to assist you.

If you have any questions about my photo that do not appear in this post, feel free to leave them in the comments. I will do my best to answer them.

To read part 1 about “The spider room”, click here.

To read part 2 about “Bug filling station”, click here.

To read part 4 about “Spinning the cradle”, click here.

To read part 5 about what to expect when entering a photo competition, click here.