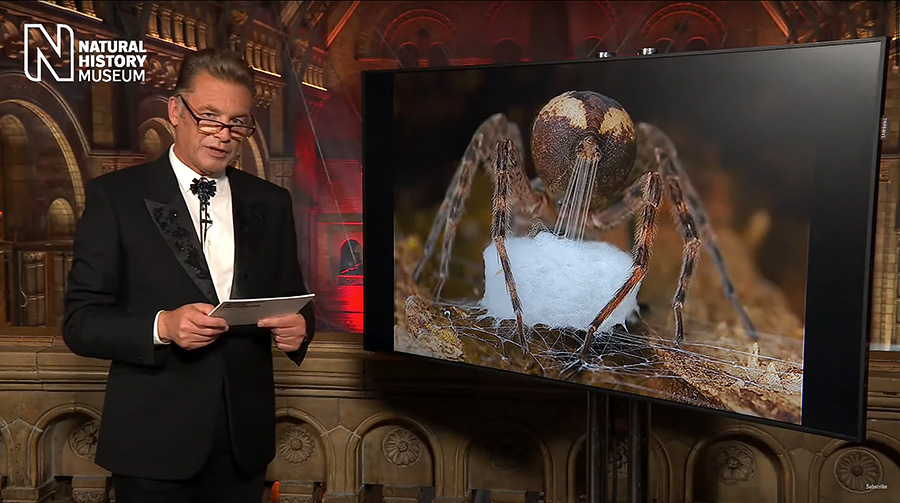

Wildlife Photographer of the Year Q&A: Spinning the cradle, Behavior: Invertebrates category winner

Up next in the series of Q&A posts about my Wildlife Photographer of the Year winning images is Behaviour: Invertebrates category winner: Spinning the cradle.

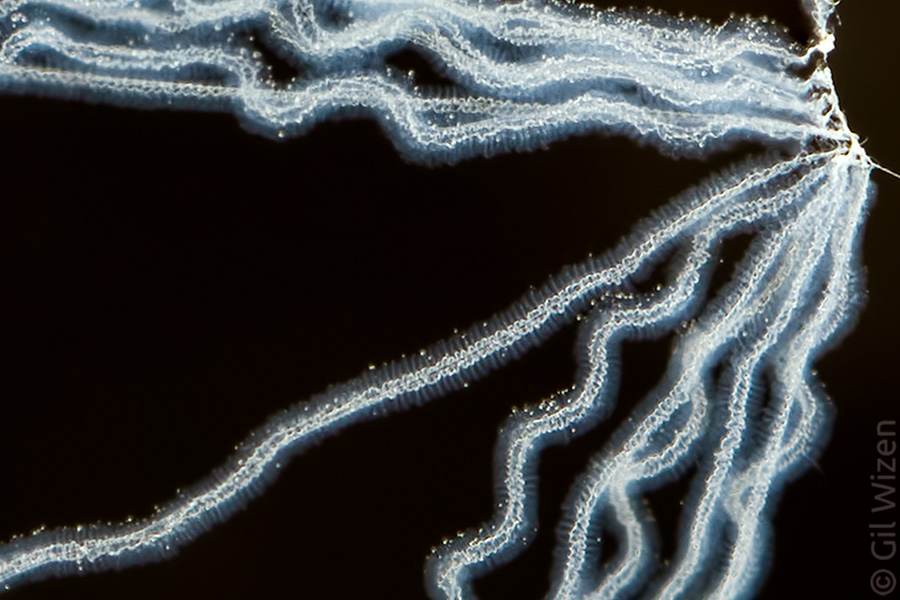

Spinning the cradle. Wildlife Photographer of the Year, Invertebrate Behaviour category winner. A female fishing spider (Dolomedes scriptus) stretches out fine strands of silk from her spinnerets for weaving into her egg sac. Ontario, Canada

You can watch the part when it appears in the awards ceremony here (timestamped)

“Spinning the cradle” really surprised me when it won in the invertebrates category. I knew the photo was good, but I never expected it to win. It is also a photo I took close to home, while on a routine walk in a forest. It goes to show the subject does not necessarily have to be something exotic or brightly colored in order to make an impact on the viewer. There are interesting things happening around us all the time. There are plenty of fascinating species very close to home, we only need to learn to find and observe them. You do not need to travel far to remote locations. Sometimes all it takes is just to look around you, you never know what you might find!

What is so special about this photo?

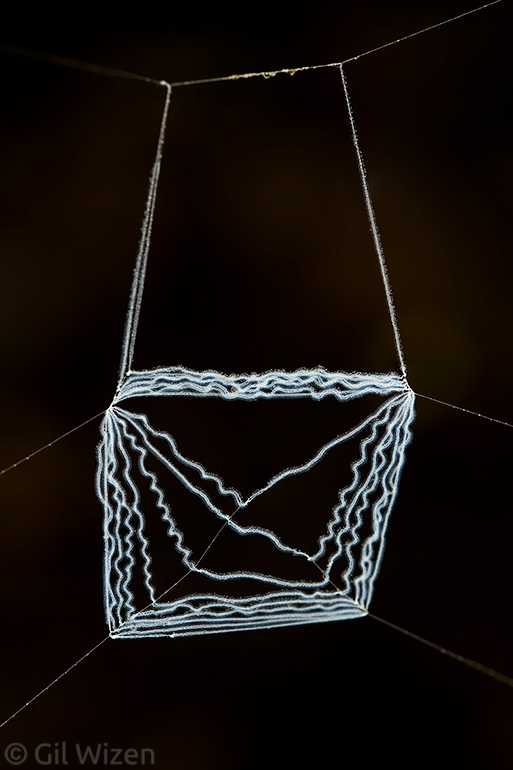

While hiking out locally and searching for arthropods for testing the Laowa 100mm 2x macro lens, I found a fishing spider (Dolomedes scriptus) under a slab of tree bark. Fishing spiders are common in wetlands where they feed on small aquatic animals (insects, amphibians, and small fish), but they are also very common in temperate forests. The spider was in the process of laying the base for an egg sac, so I thought this could be a good opportunity to observe and photograph the process, since this behavior is rarely documented. In general, spiders prefer to be hidden while constructing egg sacs. They are usually busy and distracted during the process, so they try to reduce the risk of predation to themselves and their offsprings. What I like about “Spinning the cradle” is that the photo shows the spider stretching the silk threads right before incorporating them into the rest of the forming sac. If you look closely, you can easily make out each of the separate silk strands being stretched by the spider. I have photographed weaving spiders in the past, but never in such clarity and detail. After taking the photo, I reviewed it on the camera’s back screen and I immediately knew I captured something special.

The fishing spider laying down the silk base for her egg sac, slowly working it into the shape of a bowl. This photo is rotated for easy viewing – the spider is actually facing down.

Can you explain the orientation of the photo? Something about it seems off.

“Spinning the cradle” is a rear-shot (or… a butt-shot! Did you catch that during my award acceptance speech?) of the spider stretching silk threads, but you are not really looking horizontally at the spider on eye level. Instead, the spider is standing vertically on the bark while facing down. So, in fact, the spider’s butt is facing up, and you are viewing the spider from above. I hope this makes sense.

What is the size of the spider?

This is a medium-large spider with a leg span of 6cm.

How were you able to take this photo without disturbing the spider?

Any disturbance could have caused the female spider to stop spinning and abandon her project. The main challenge here was to keep the tree bark the spider was on very steady and avoid breathing on the spider while I was photographing the behavior. We often take our breathing for granted. Most spiders have rather poor vision, but they can sense when a large animal is breathing right next to them, and will try to flee the area. So I carefully leant on the tree in a bit of an awkward position, placing the trunk between my legs to keep my body stabilized. Then I steadied the bark with my left hand and gripped the camera in my right while holding my breath, and started photographing.

An animation showing the spider in the process of incorporating silk into the forming egg sac

Can you describe the spinning process? How does the spider make a spherical sac out of silk threads?

The movements of the spider’s spinnerets in action reminded me a lot of human fingers when weaving. The spider has complete control over the direction and density of the silk threads coming out of each spinneret. It is quite fascinating to watch. The spider starts with a flat circular base, and spins around in circles while adding more silk to its outer side, slowly forming walls. As the spider continues to build upwards, the silken disc gradually grows into a bowl shape. The spider continues to stretch and incorporate more silk until the bowl is deep enough to accept the egg mass. Then the spider stops, spends a few good moments laying the eggs, and quickly (and I do mean quickly) starts spinning again, this time carefully rolling the sac from side to side while tightening the silk threads, forcing its shape into a sphere. Once the sac is sealed, the process is complete.

The spider moments after laying her eggs. Note the smaller size of the abdomen compared to the previous photo.

How long did the spinning process take?

Spinning the egg sac, laying the eggs, and sealing the sac is a long process and requires a great investment of energy from the female spider. The process takes about 1-2 hours, during which the spider is focused on the project and is in fact vulnerable to attacks. This is the reason why spiders usually spin their egg sacs in a hide (like in this case, under bark), unexposed to potential predators and parasitoids.

What did you do after the spider finished spinning its egg sac?

After about an hour, the spider completed most of the sac and was getting ready to lay its eggs inside it, at which point I snapped a couple of final photos, slowly moved the bark back in place and left the animal to its business. There was no need to cause damage to the next generation of fishing spiders for the sake of obtaining more photos. The attentive mother will carry the sac with her until the eggs inside hatch and the hundreds of spiderlings disperse.

We like the photo! Can we buy a print from you?

Of course. Contact me and I will do my best to assist you.

If you have any questions about my photo that do not appear in this post, feel free to leave them in the comments. I will do my best to answer them.

To read part 1 about “The spider room”, click here.

To read part 2 about “Bug filling station”, click here.

To read part 3 about “Beautiful bloodsucker”, click here.

To read part 5 about what to expect when entering a photo competition, click here.

Stay tuned for the next posts in this series!